Orientation vs. Optimization

Why Trajectory Is More Important Than Scale

Founders are constantly flying in a dozen different directions. There's always something that needs fixing, improving, or reinventing. In addition, everything is also trying to kill you. Co-founders want more recognition, investors want more ownership, employees want more compensation and competitors just want you to die quickly. Amid this chaos, founders have to focus and rocketone of the most critical skills to develop is knowing when to focus on orientation (your direction) versus optimization (your efficiency). I've found that many founders get this balance wrong, often with costly consequences.

The Rocket Ships & Startup

Let me offer an analogy that has served me well. Building a [venture-backed] startup is remarkably similar to launching a rocket. Both rockets and startups are built for speed, not comfort. After you launch a rocket, there are only two possible outcomes:

It reaches orbit (success)

It explodes (a learning opportunity)

There's very little middle ground. Unlike vehicles built for versatility or comfort, rockets are singularly designed machines – literally a seat strapped to explosives in a metal tube, hurtling through the atmosphere at thousands of miles per hour. They don't have airbags. They don't have air conditioning. They don't have cupholders or entertainment systems. They have one purpose: to reach orbit as quickly and reliably as possible.

Startups function in much the same way. They're not designed for comfort or balance. They're designed to solve one specific problem better than anyone else, and to reach escape velocity before their funding (rocket fuel) runs out.

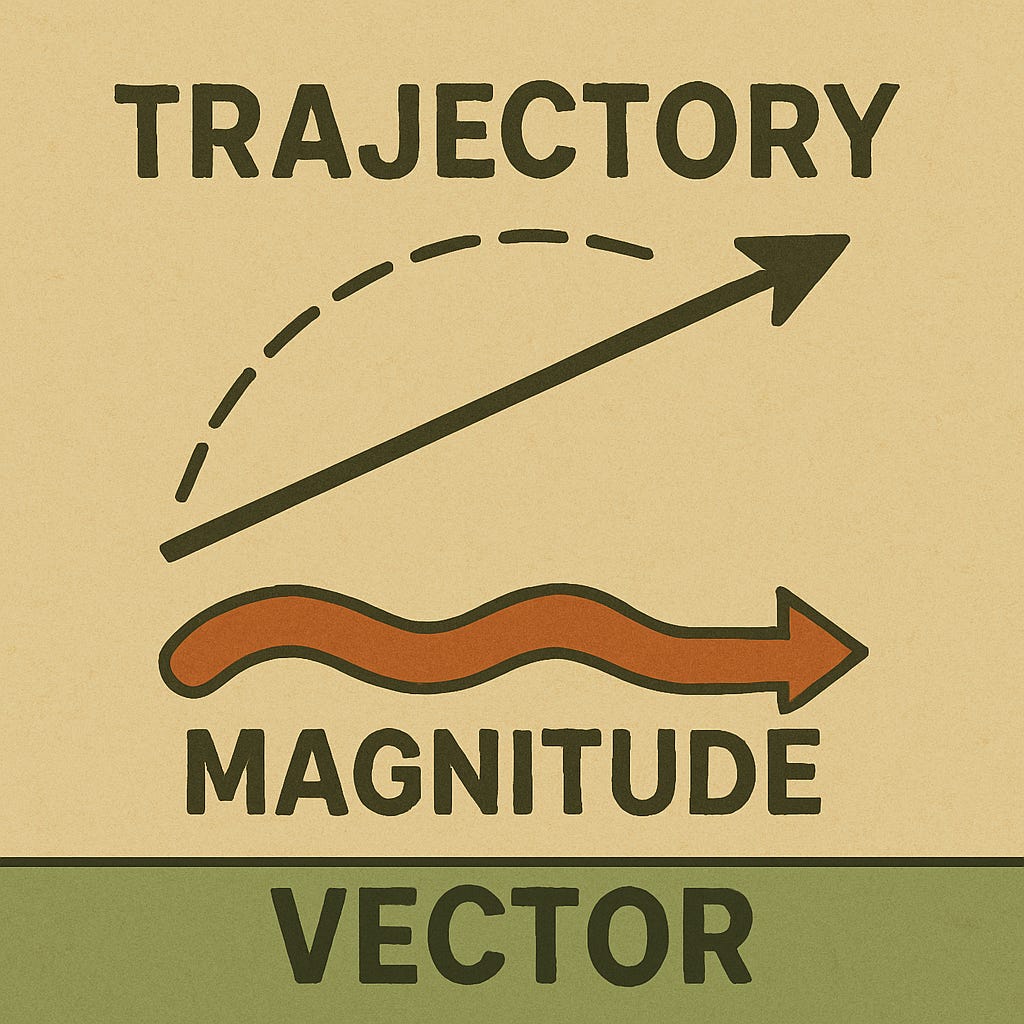

Understanding Your Vector: Trajectory and Magnitude

To get more technical for a moment, a rocket travels on a vector, which has two critical components:

Trajectory (Orientation): The direction your rocket is pointed

Magnitude (Optimization): How fast and efficiently you're moving in that direction

This distinction is crucial for founders to understand. Orientation is about making sure you're building something people actually want and that you're pointed toward a viable market. Optimization is about improving your speed, efficiency, and execution once you know you're headed in the right direction.

The fundamental mistake many founders make is obsessing over path optimization before establishing the right trajectory. They perfect features for products no one wants. They optimize conversion funnels for services with no product-market fit. They hire specialists to squeeze efficiency out of processes that may not even matter to their core business.

Optimizing Too Early

I've witnessed this pattern repeatedly. A founding team becomes captivated by questions like:

"Should our call-to-action button be blue or green?"

"Can we improve our onboarding flow to convert 2% better?"

"Should we switch cloud providers to save 5% on infrastructure costs?"

These questions aren't inherently wrong. They'll matter eventually. But timing is everything. When you're pre-product-market fit, these optimizations are often a dangerous distraction from the more existential questions:

"Are we solving a real, painful problem?"

"Do customers actually want what we're building?"

"Is our business model viable at scale?"

"Is the market large enough to support our ambitions?"

Consider the fate of countless failed startups with beautifully optimized products that no one wanted. Quibi comes to mind – they optimized a short-form video platform with billions in funding, top Hollywood talent, and flawless execution. What they failed to confirm was whether the market actually wanted yet another streaming service with arbitrary content length constraints.

Scale Changes Everything

There's a simple mathematical reality that makes early optimization even less sensible: the benefits of optimization are directly proportional to your scale.

When you have 100 users and improve conversion by 1%, you've gained exactly one additional user. That's hardly worth a week of A/B testing and design debates.

But when you have 100 million users? That same 1% improvement represents a million additional people – suddenly those optimizations become incredibly valuable, potentially worth millions in revenue.

This is why founding a company oddly rewards procrastination on most optimization problems:

At 10 customers, a clunky manual onboarding process is perfectly acceptable

At 100 customers, you might need basic automation

At 1,000 customers, you need dedicated systems

At 1,000,000 customers, you need a team of specialists constantly optimizing the process

Trying to build systems for 1,000,000 customers when you have 10 is a recipe for wasted resources and premature scaling – arguably the primary killers of promising startups.

Selective Obsession and Selective Ignorance

To start a company at all, you need to be somewhat obsessive – you've seen a problem that millions of people have effectively ignored and decided "this must be fixed." That obsessive attention to a problem others overlook is often what creates breakthrough innovation.

Yet successful founders must simultaneously develop the discipline to ignore countless imperfections in their business. They must be willing to ship products that aren't quite ready, implement processes that aren't fully refined, and make decisions with incomplete information.

This cognitive dissonance – being simultaneously obsessive about your core value proposition while willfully blind to a thousand small inefficiencies – is mentally taxing. It doesn't come naturally to most people, especially the perfectionist personalities that are drawn to entrepreneurship.

Orientation Before Optimization

So how do you know when to focus on orientation versus optimization? Here's a framework I've found helpful:

1. Pre-Product-Market Fit: 90% Orientation, 10% Optimization

In the earliest stages, your singular focus should be finding product-market fit. This means:

Talking to customers constantly

Shipping minimum viable features rapidly

Testing core assumptions weekly

Being willing to pivot when the data demands it

Focusing on the 20% of features that deliver 80% of the value

The small amount of optimization at this stage should be limited to removing obvious friction that prevents you from learning. If your signup flow is so broken that users can't even test your product, fix it. Otherwise, embrace the rough edges.

2. Early Growth: 70% Orientation, 30% Optimization

Once you've found initial product-market fit, you enter a phase where you're still refining your direction, but can begin addressing the most painful inefficiencies:

Expand your core offering to serve adjacent needs

Fix the most glaring user experience issues

Implement basic automation for repetitive tasks

Develop initial metrics and dashboards

Begin building repeatable sales and marketing processes

3. Scale-Up: 30% Orientation, 70% Optimization

As you achieve significant scale, the balance shifts dramatically toward optimization:

Relentlessly improve key conversion metrics

Build specialized teams focused on efficiency

Continuously refine and automate processes

Optimize customer acquisition costs

Fine-tune pricing and packaging

Expand to adjacent markets and customer segments

4. Market Leader: 50% Orientation, 50% Optimization

Interestingly, once you become a dominant player, the focus on orientation often increases again. This is because large companies must continuously reinvent themselves to avoid disruption:

Invest in innovation labs and skunkworks projects

Explore new business models and revenue streams

Anticipate industry shifts and changing customer needs

Acquire or build potentially disruptive technologies

Balance optimization of the core business with exploration of new frontiers

Learning to Live with Imperfection

Perhaps the hardest part of this journey is learning to live with imperfection. Your product will never be "done." Your processes will never be completely optimized. There will always be bugs to fix, features to add, and efficiencies to gain.

The key is developing the wisdom to know which imperfections matter right now, and which ones can wait. This requires both humility to recognize what you don't yet know, and confidence to stay the course when you believe in your direction.

Refine Your Trajectory Before Maximizing Your Speed

Before optimizing your rocket for speed, make absolutely certain it's pointed toward orbit. No amount of efficiency will save a perfectly optimized rocket that's flying in the wrong direction.

In practical terms, this means:

Validate your core value proposition before perfecting your execution

Confirm product-market fit before optimizing conversion rates

Ensure your unit economics work before scaling your marketing

Verify customer satisfaction before automating your processes

Test your core assumptions before building complex systems

Remember that the most successful startups aren't always the ones with the most elegant code, the prettiest interfaces, or the most efficient operations from day one. They're the ones that identified a compelling customer need, built a solution that addressed it effectively, and oriented themselves toward a large, growing market.

Only after getting the orientation right did they turn their attention to optimization – and by then, they had the resources, data, and market validation to make those optimizations truly worthwhile.

If your rocket ship is on the launchpad, make sure it's pointed toward the stars before you throttle up the engines.

Thanks! And wow, your seasoned hire observation really resonates. I have definitely run into that problem in the past. Sometimes those hires look great on paper, but rarely work in practice. I've seen so many early teams get bogged down building the 'right' processes to accomplish the wrong objectives. I have not finished 'Be the Go-To' yet, but the first quarter of the book has been solid - seems like we're thinking about similar challenges from complementary angles. Thanks again for the note. 😎

This is a fantastic article, Collin. So true. I echo this sentiment in my book, Be the Go-To, with the sequencing of phases in the Apollo Method for Market Dominance -- operational efficiency doesn't become a focus until the Navigate phase after there is market traction. (I enjoyed the rocket analogy for obvious reasons. :)

In my experience, startups staffed by "seasoned people" from big-name companies are more prone to optimize-itis unless the advisors around them keep their innate efficiency-seeking impulses in check. They have come from environments in which there is infrastructure and a slower pace (HR processes, approval processes, mainstream tools, expectations of perfectionism, etc). The sloppy, seat-of-the-pants nature of startups in Orientation mode, as you put it, makes them uneasy, because they know there is a "better way to do it."

Hope to see this article get lots of attention!