Being Right Is Not a Strategy

The Most Dangerous Assumption in Business (And Life)

There’s a video circulating that I still can’t get out of my head. A woman in Minnesota, an American citizen, a mother in her thirties, had a confrontation with federal agents in Minnesota. The details are still emerging, but from the videos released, she appeared to try and leave the confrontation, which was arguably within her rights. According to the reporting, she was there protesting ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement), motivated by causes she believed in. She tried to drive away. But a federal agent shot her three times. She died.

I don’t know all the specifics of her background nor what led to that exact moment. What I do know is this: she probably felt that what she was doing was right. And she’s still dead.

This event made me think a lot about my own experiences both as an individual and as a founder.

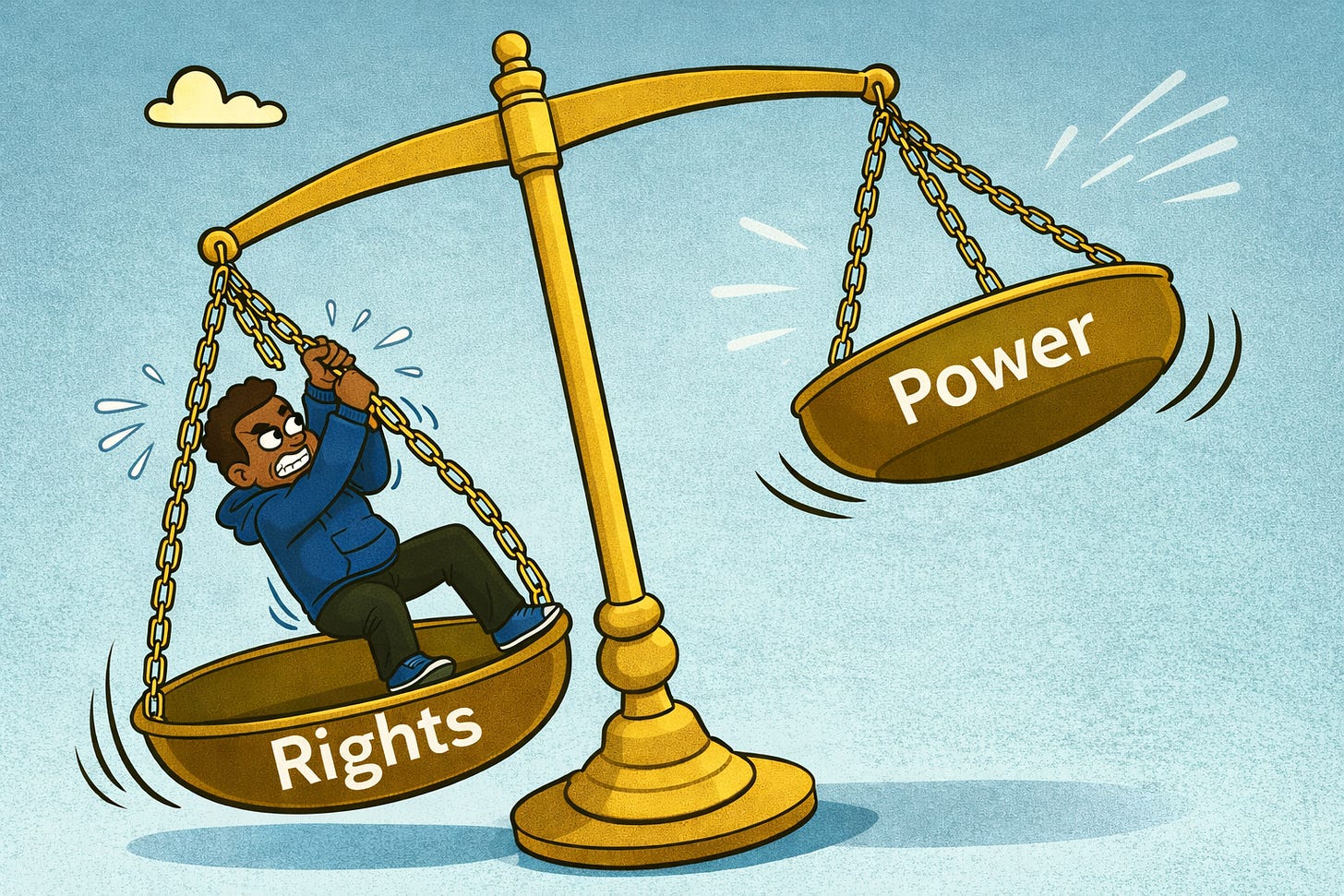

This idea—that you can be right and still lose—has long been understood in my community in America. It’s a hard-earned wisdom passed down through generations: just because the law says you have a right doesn’t mean that right will be respected, protected, or enforced. Just because you should be able to do something doesn’t mean there won’t be consequences, penalties, or violence for trying.

For many of us, this is an abstraction. A theoretical problem. Something we might debate in a classroom or acknowledge in passing. But for others, it’s survival knowledge. It’s the difference between coming home and not coming home.

And I think there’s a profound lesson here that extends far beyond the immediate tragedy of this woman’s death—a lesson that startup founders, in particular, need to internalize.

We operate in a world that loves to talk about rights. Intellectual property rights. Employment rights. Contractual rights. We build entire business strategies around the assumption that because we’re right, we’ll win. That the law will protect us. That the patent will be enforced. That the competitor won’t do that horrible thing because, well, they’re not supposed to.

This is naive. It’s a privileged view of how the world actually works.

Yes, the law may say that the person you classified as a contractor should really be an employee. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to lose that fight, or that it will restore fairness to the workplace. Yes, the law may say you have a patent and that someone shouldn’t steal your idea and embed it in their own product. But if you don’t have the resources, the stamina, or the leverage to enforce that patent, you might be completely right and still watch your company die.

The market doesn’t care about should. It cares about can and will.

I’ve seen this play out dozens of times across the companies I’ve worked with and invested in. A founder builds something genuinely innovative, files for patent protection feeling incredibly accomplished to be able to put “patent pending” all throughout their deck, and then watches in horror as a well-funded competitor copies it wholesale. “But we have the patent!” they protest. Sure. And the competitor has $50 million in the bank and a legal team that will drag you through litigation until you run out of money. You’re right. You’re also losing.

Or consider the founder who discovers their acquirer negotiated in bad faith, clearly violating the terms of the letter of intent. “We’ll sue them,” becomes the rallying cry. Maybe you will. Maybe you’ll even win. But in the three years it takes to litigate, your company will have burned through its remaining capital, your team will have left, and your technology will be obsolete. You were right. You still lost.

The same dynamic plays out in talent disputes. A key employee leaves to join a competitor, clearly violating their non-compete agreement. You’re absolutely right that they breached their contract. But if enforcing it means spending six months in court proceedings, distracting your team, and signaling to other employees that you’re litigious, what have you really won?

This isn’t an argument for nihilism or for abandoning principles. It’s an argument for clear-eyed realism about power and leverage.

Being right is not a strategy. Being right is a starting point.

The strategic question is always: given that I’m right, do I have the ability to enforce that rightness? And if I don’t, what does that mean for how I need to operate?

Sometimes it means you need to build different defenses. If you can’t rely on patent protection because you don’t have the resources to litigate against well-funded copycats, then your competitive advantage needs to come from speed of execution, network effects, or brand loyalty—things that can’t be easily copied regardless of IP law.

Sometimes it means you need to be more paranoid. You can’t just assume that because your competitor signed an NDA, they won’t steal your pitch and build it themselves. You need to think through what you’d do if they did—and whether you’d have any real recourse.

Sometimes it means you need to pick your battles. Yes, that former employee violated their non-compete. But is the fight worth the distraction and the cultural damage? Sometimes the right answer is to let it go and focus on building something so much better that their departure becomes irrelevant.

And sometimes—and this is the hardest one—it means you need to acknowledge that the game itself is rigged, and you need to find a different game to play.

The woman in Minnesota probably thought she had the right to drive away. She probably did have that right. But the federal agents had guns, and they used them. She was probably right about the law. She was wrong about whether that would matter for her.

For startup founders, the stakes are obviously different. No one’s life is on the line when a patent dispute goes south or when a competitor plays dirty. But the underlying dynamic is the same: in the short term, power matters more than rights.

The market is not a court of law. It’s not bound by rules of evidence or precedent. It doesn’t care about should. A well-funded competitor can steamroll you even when you’re completely in the right. A bad faith acquirer can tie you up in litigation until you’re forced to accept terrible terms. An employee can walk away with your trade secrets, and your only recourse might be a years-long legal battle that costs more than your company is worth.

This is why the best founders are paranoid. Not in a debilitating way, but in a realistic, eyes-wide-open way. They understand that being right is necessary but not sufficient. They build their strategies assuming that some percentage of people will not play by the rules, that some competitors will copy them despite IP protections, that some partners will negotiate in bad faith.

They build defensible businesses not because the law says they should be defensible, but because they’ve made them so difficult to attack that it doesn’t matter what the law says.

They move fast not just because speed is good in the abstract, but because speed is one of the few competitive advantages that can’t be legislated away or copied by a competitor with deeper pockets.

They cultivate relationships and reputation because when the chips are down and the legal system is too slow or too expensive to help, those relationships might be the only leverage they have.

The tragic lesson from Minnesota is one that too many people have learned too many times: you can follow the rules, you can be in the right, you can do everything you’re supposed to do—and you can still lose everything.

For founders, this should be a wake-up call. Don’t build your company on the assumption that being right will be enough. Don’t assume the law will protect you. Don’t assume your patent will be enforced, your contracts will be honored, or your competitors will play fair.

Be right. But be right and prepared to fight for it with every resource you have. Be right and paranoid. Be right and ruthless about building real defensibility.

Because in the end, the market—like those federal agents—doesn’t care whether you’re right.

It only cares who has the power.

Thanks for being a Perishable Knowledge subscriber.

If you are getting value from my blogs, I’d appreciate it if you share this post with someone who will enjoy it. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing.)

I’d also argue that, similarly, being the best has never been a strategy in America either. From the Negro Leagues to recent elections, it’s clear that the game has never really been about being right or being the best, but about trying to stack the odds in your favor in such a way that success appears inevitable enough to fast followers that they begin to “side” with the players who look like future winners.